Data integrity is the foundation for store operations to contribute to maintenance program performance.

Here’s a test. Go into your parts storeroom and try to find a part that you can’t match to any piece of equipment in your plant. It’s a very rare plant that doesn’t have a box, bin or even shelves full of parts that no one is quite sure exactly where they go, but the storeroom is keeping, “just in case.” Even with sophisticated database software in place, we have seen a case where someone found a bearing that could not be identified, but it was stamped with a date of manufacture as 1956. What are the chances the original machine it belongs to is still operating?

Years of “thinking Lean” led many manufacturers to install systems offering visibility to the flow of direct production parts from suppliers to the assembly line. Very few, however, have had the same discipline or success tracking indirect inventory or maintenance, repair, and operations (MRO) data on all the bearings, belts, motors, cleaning supplies, gloves or hair nets required to keep the production line going. For instance, a car might have 15,000 to 20,000 direct parts, but the assembly lines used to build that same vehicle requires many more indirect parts in a storeroom to keep those assembly lines moving. And although MRO parts and supplies might make up only a small percent of expenditures by a plant, they generate 95 percent of the purchase transactions.

For a stores operation to be effective, it has to have the trust of the maintenance department. To earn that trust, MRO data must have integrity; meaning a disciplined process that ensures accuracy and consistency of data. Data integrity is the foundation for stores operations to contribute to maintenance program performance.

Quite simply, if you can’t be sure about finding the right parts at the right time, you are putting planned maintenance compliance, if not the performance of the whole plant, at risk. Many maintenance technicians address this risk by keeping their own unofficial and potentially unauthorized stores; the practice is so common that many plants have an “amnesty day” when technicians can safely reveal those “private” stashes of parts.

If you are not convinced you have a problem at your plant, here are a few metrics to track:

- Number of planned maintenance projects delayed by missing supplies (parts, lubricants and other consumable items needed for the work)

- Percent of maintenance time devoted to identifying required supplies for each job and delivering them ready to install at the job site

- Amount of time maintenance staff spend planning what may be required for planned work, ordering parts, checking availability and assembling supplies themselves.

It is possible to manage maintenance supplies with the same discipline companies use to manage direct materials. For any needed MRO supply, you should be able to buy it, receive it, put it away, find it, and issue it. However, establishing data integrity of a storeroom database takes more than simply installing software.

Software migration requires a systematic approach that starts with an assessment of its current state. Here are specific questions to ask about your inventory system:

- Is every item in the storeroom in your system? And will it be tracked consistently as it is issued for use in the plant?

- Is there a use for every part?

- Is every part identified not just with a unique number, but a unique description or set of specifications?

- When a part arrives do you know exactly where it goes to be stored? Or where to get it when needed?

- Can you identify the source of the part, price, purchased date and its warranty terms?

- Can you link the part to a specific process, piece of machinery and location in the plant?

- Can you track the usage of the part and its likely lifecycle?

- Is the part linked to a preventive maintenance schedule so it can be kitted and staged at an appropriate time?

- Can you query the database to generate useful reports to measure performance?

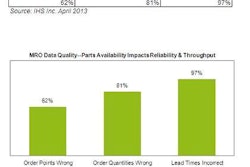

Databases used to manage MRO parts must be properly updated to stay intuitive. Many times we see information stored in the CMMS as static or minimally maintained. Businesses don’t always try to interface the database to maintain critical data points of information normally obtained by Purchasing and Accounts Payable. Information changes very often, and the database used to manage parts also needs to change. IT departments are busy developing and maintaining systems for the finished goods and direct material used to make them. Maintenance departments don’t always have a budget to manually gather and update all the changes that occur, sometimes on an hourly basis. Let’s face it, why spend money on systems and tasks that do not make money? This all leads to inaccurate cost control, unusable inventory, excessive purchases of non-stock items, and private caches of items.

If you decide to either upgrade a software system, or improve the operating procedures of the people who use it, then treat it as a significant change. Apply the same tools and discipline you use when analyzing the production value stream; after all, the maintenance value stream affects production performance.

Bring stakeholders in before the purchase to test drive demonstration software and review procedures. Or use a group of “beta testers” to test procedures before implementing them plant-wide. There is a tremendous pool of knowledge on the shop floor, and it’s often a production worker or receiving clerk that discovers the shortcomings of new software or new procedures.

Another issue to keep in mind is that people with different responsibilities will use the new system – so it has to meet many needs that may not be neatly aligned. Because every situation is unique, any improvement in a database is likely to require accommodations or compromises by all users. At the same time, it’s often necessary to reorganize or renovate storage spaces, and set up and train staff in new procedures.

Any database improvements are likely to have cost benefits beyond maintenance and reliability. They can reduce inventory costs and express freight charges, for example. In fact, the transition to a well-managed database should be set up to provide a company with valuable business intelligence. A high-performing system can generate metrics that lead to real improvements in plant efficiency and lowering overhead. Here are a few key performance indicators (KPIs) that manufacturers might pull from their databases:

- Inventory – aggregate cost

- Inventory turns – how much is needed to maintain a steady state

- Availability of critical spare parts

- Lead times needed to plan properly

- Fill rate levels needed to complete job requests

In short, any software migration or systems improvement should be carefully planned and staged. It’s not really just a transition. It’s generally an extreme makeover that doesn’t just change the operations of the storeroom. It may alter the operating culture of the plant. The results are worthwhile, but the implementation has to be done thoughtfully and well.

About The Authors

Mike Dyson is Chief Business Intelligence Officer, for Storeroom Solutions, Inc. He has more than 30 years of experience in multi-million dollar operations across diverse markets including implementation of large integrated supply chain management programs using PeopleSoft and SAP. He has a wide range of application knowledge mostly within the aerospace, electronics, automotive and exotic materials community. His executive management experience encompasses working with large enterprise clients such as Northrop, Lockheed, Ingersoll-Rand, TRW, AlliedSignal (Honeywell), Hughes (Raytheon), and General Dynamics to name a few.

James Rogers is Business Unit Director, Maintenance & Reliability Services, for Storeroom Solutions, Inc. He has dedicated his career to reliable plant performance, with experience ranging from “mega projects on a global scale” from his start with engineering and construction behemoth Fluor Corporation to owning and operating a South Carolina-based plant services company. Through all of his experiences, James learned not only the critical dependency on stores operations to achieve the maintenance mission, but how to convert stores from a common process constraint to a performance catalyst enabling maintenance to deliver a reliable plant.